Cy Twombly

Discover a curated selection of museum-quality Cy Twombly art for sale, featuring original prints, limited editions, and rare works.

"The past is a springboard for me... Ancient things are new things. Everything lives in the moment; that's the only time it can live, but its influence can go on forever."

Edwin Parker "Cy" Twombly Jr. (1928-2011, Lexington, Virginia) was an American artist whose distinctive style merged painting, drawing, and writing in large-scale works characterized by expressive mark-making, classical references, and poetic sensibility. After studying at the Art Students League in New York and Black Mountain College under Franz Kline and Robert Motherwell, Twombly developed a unique visual language that departed from the dominant Abstract Expressionism of the period. In 1957, he settled in Italy, where classical mythology, Mediterranean history, and European culture profoundly influenced his practice.

Twombly's oeuvre is defined by scrawled calligraphic marks, scribbles, and text fragments floating across pale surfaces that evoke ancient walls or palimpsests. His "blackboard" paintings of the late 1960s featured looping, cursive white lines on dark gray backgrounds suggestive of handwriting exercises. Throughout his career, Twombly engaged deeply with literary and mythological themes, often incorporating poetic fragments and classical references into his compositions. His later works, especially his monumental "Bacchus" series with its explosive red loops, display remarkable vitality and gesture. Working between Rome, Gaeta (Italy), and Lexington (Virginia), Twombly created a body of work that bridges ancient and modern sensibilities, constructing a deeply personal visual poetry that influenced generations of artists engaging with language, history, and abstraction.

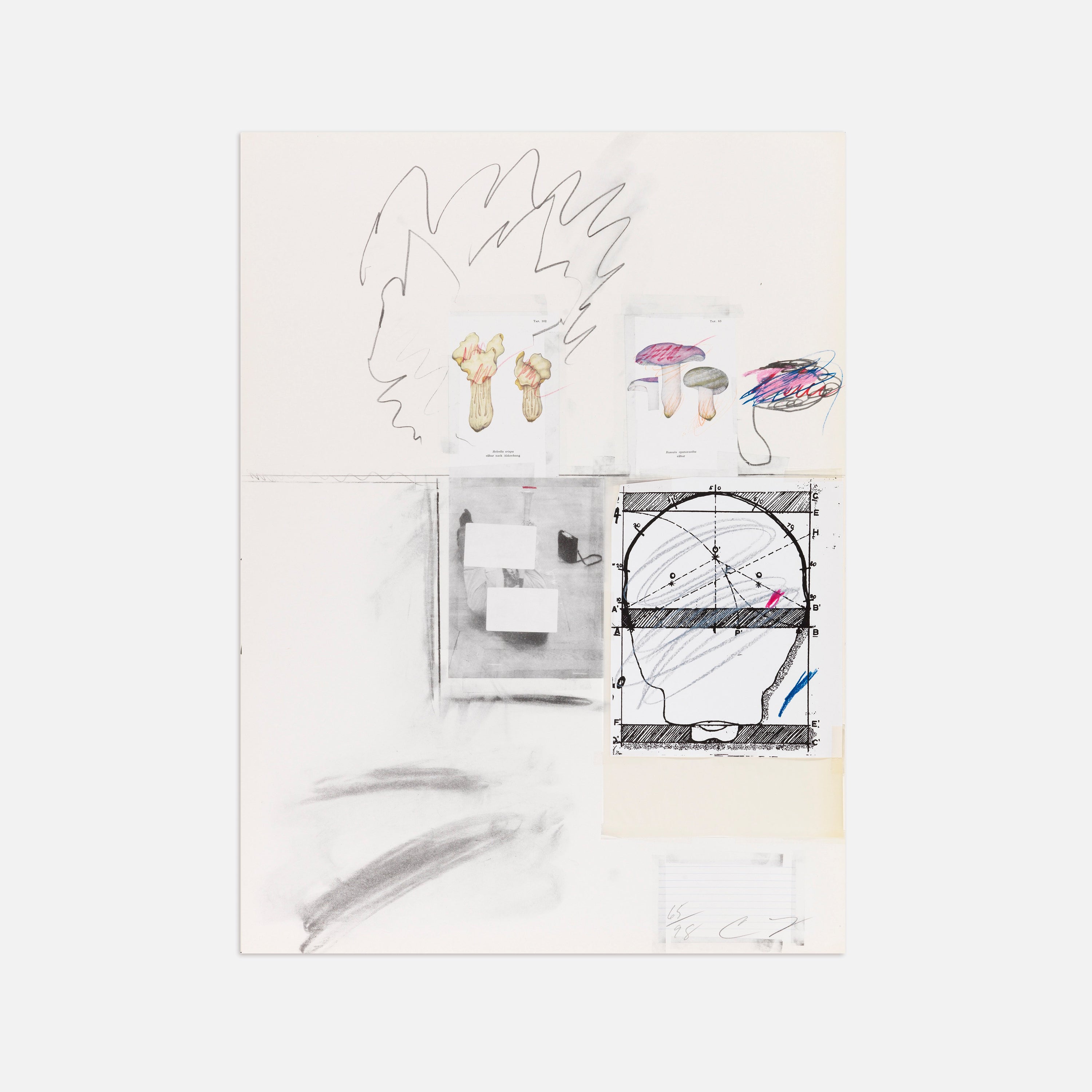

Cy Twombly, Natural History Part II: Mushrooms, 1974

-

Fagus Silvatica, from Natural History Part II: Some Trees of Italy, 1976Sold

Cy Twombly

Sold -

Quercus Robur, from Natural History Part II: Some Trees of Italy, 1976

Cy Twombly

$19,500 -

Castanea Sativa, from Natural History Part II: Some Trees of Italy, 1976

Cy Twombly

$19,500 -

Quercus Ilex, from Natural History Part II: Some Trees of Italy, 1976

Cy Twombly

$19,500 -

Laurus Nobilis, from Natural History Part II: Some Trees of Italy, 1976

Cy Twombly

$19,500 -

Tilia Cordata, from Natural History Part II: Some Trees of Italy, 1976

Cy Twombly

$19,500 -

Ficus Carica, from Natural History Part II: Some Trees of Italy, 1976

Cy Twombly

$19,500 -

Plate X, from Natural History Part I: Mushrooms, 1974Sold

Cy Twombly

Sold -

Plate IX, from Natural History Part I: Mushrooms, 1974Sold

Cy Twombly

Sold -

Plate VIII, from Natural History Part I: Mushrooms, 1974

Cy Twombly

$18,000 -

Plate VIII, from Natural History Part I: Mushrooms, 1974Sold

Cy Twombly

Sold -

Plate VI, from Natural History Part I: Mushrooms, 1974Sold

Cy Twombly

Sold -

Plate V, from Natural History Part I: Mushrooms, 1974Sold

Cy Twombly

Sold -

Plate IV, from Natural History Part I: Mushrooms, 1974Sold

Cy Twombly

Sold -

Plate III, from Natural History Part I: Mushrooms, 1974

Cy Twombly

$16,000 -

Plate II, from Natural History Part I: Mushrooms, 1974Sold

Cy Twombly

Sold -

Plate I, from Natural History Part I: Mushrooms, 1974Sold

Cy Twombly

Sold

Sell Cy Twombly Art

Same-day, confidential, no-obligation purchase offers for your Cy Twombly prints and editions.